George Butterworth - a biography

by Robert Weedon

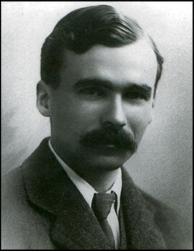

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was both on 12th July 1885 to a comfortable upper-middle class family.

His father Alexander Kaye Butterworth was a solicitor for the Great Western Railway and his mother

Julia had been a professional soprano before her marriage.

Although born in London, most of George’s youth was spent in Yorkshire after his father was promoted to be solicitor

and later general manager of the North Eastern Railway company, and at the premiere of his Shropshire Lad rhapsody,

he was still referred to as a ‘Yorkshire composer’.

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was both on 12th July 1885 to a comfortable upper-middle class family.

His father Alexander Kaye Butterworth was a solicitor for the Great Western Railway and his mother

Julia had been a professional soprano before her marriage.

Although born in London, most of George’s youth was spent in Yorkshire after his father was promoted to be solicitor

and later general manager of the North Eastern Railway company, and at the premiere of his Shropshire Lad rhapsody,

he was still referred to as a ‘Yorkshire composer’.

As was typical for a boy of his class and background, George was first sent to a local preparatory school at Aysgarth,

where he began studies of piano and organ, before attending Eton College (1899-1904).

Letters from his housemaster at Eton hint in typically starchy fashion that his academic attainment throughout his

teenage years was poor, although he was already composing and involving himself in music, with several hymns surviving

in the scrapbooks his father compiled.

A now lost orchestral Barcarolle (boat song) was performed by the school orchestra in April 1903.

It was only in his final year that George settled down to study for entrance to university.

He gained a place to read Greats at Trinity College, Oxford in 1904, with his father intending George to follow him into the legal profession.

However, as at Eton, George did not focus rigidly on his academic studies, eventually gaining a third class degree in 1908.

Instead, Butterworth used his time at Oxford to pursue various musical avenues, the most fruitful being that of folksong collection.

The movement to collect folksong had been ongoing since the turn of the century, part of the increased interest in musical

nationalism in Western art music. From 1900 to the later 1920s, there was a concerted effort by composers and

musicologists headed by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp to preserve the unique ‘traditional’

music of England which had been part of an unwritten oral tradition passed down between generations of singers and families.

They rightly feared that these working-class songs would be lost with the rise of the gramophone players,

affordable upright pianos and printed sheet music.

After meeting Ralph Vaughan Williams at Oxford, George became a keen collector of these folk songs,

joining the Folk-Song Society in 1906 and eventually collecting more than 450 items including songs,

dance tunes and dances, many of which he was to arrange for performance and collate in a series of joint publications with Cecil Sharp.

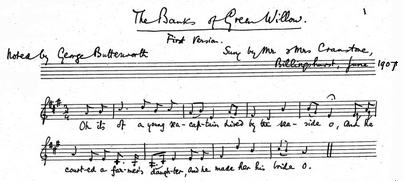

The majority of George's folk song manuscripts are deposited at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. They have recently digitised

many of his folk manuscripts, which enables us to see the origins of some of his works.

For example, here is a hand-notated

folksong "The Banks of Green Willow" which George collected at Billingshurst, Sussex

in June 1907, the melody of which he was adapt and incorporate into his famous orchestral rhapsody of the same name.

Along with Sharp and Vaughan Williams, George was an early adopter of new analogue recording technologies,

and made recordings of many of the singers he met using

portable phonographs which recorded performances onto wax cylinders. Many of these have survived, for example

this

is a recording in the British Library Sound Archive of another version of "The Banks of Green Willow" recorded in 1909.

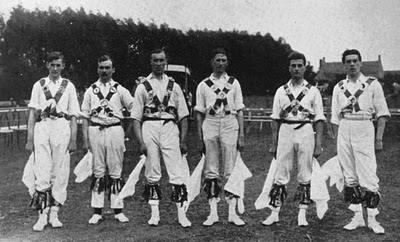

George was particularly keen on traditional English folk dances, and he became a founder member of the English Folk Dance Society in 1911.

He was part of a team that demonstrated these dances around the country and there is even surviving

Kinora film footage

of him from circa 1912 athletically demonstrating a variety of folk dances in full morris gear. A Kinora was essentially a

very early home video camera.

Note the enjoyable reaction at 3:50 when George accidentally bumps into Cecil Sharp.

Dancing was clearly a passion for George, and according Michael Barlow, he once declared

"I'm not a musician, I'm a professional dancer". In this photograph of Cecil Sharp's demonstration morris side in 1911 we see left to right

D. N. Kennedy, George Butterworth, James Patterson, Perceval Lucas, A. Claud Wright and George Jerrard Wilkinson.

However, like almost all of the university-educated composers of the Victorian/Edwardian era, a perceived threadbare career

in music was not his parents’ intention. Music was a hobby or an enjoyable diversion, but a musical

career was still considered in some quarters a ‘trade’.

Following a path similar to Hubert Parry and Ralph Vaughan Williams, George had (in the words of Stephen Banfield)

a ‘stereotypical conflict’ with his father after announcing that he did not wish to enter into one of the recognised professions, in this case law.

Perhaps his father’s fears were justified, as without his family’s patronage, George struggled to establish himself as a composer.

The years 1908-9 were taken by writing musical criticism for The Times under J.A. Fuller Maitland and then

teaching music at Radley College, an independent boys school in Abingdon, from 1909-1910, where his shyness was evident to colleagues.

One remarked that “Few men can have been worse at making an acquaintance or better at keeping a friend.”

His famous settings of poems from A.E. Housman's A Shropshire Lad, the Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad

and Bredon Hill and other songs date from this period.

Housman's melancholic poetry collection was an inspiration for a whole generation of composers and

was also set to music by Somervell, Moeran, Ireland, Vaughan Williams, Gurney and others.

However, George Butterworth's setting was the only one which Housman (who allowed but disliked settings of his poetry) tacitly approved of.

In May 1910, George passed the first of three examinations for the Oxford BMus degree (music degrees in this period were often

more akin to correspondence courses), but he pursued this no further. However, work on these and, presumably his songs, which were

already published and gaining popularity, were enough to gain him entry to the

Royal College of Music where the organist Walter Parratt was his principal tutor and Charles Wood his harmony tutor. It was during this period (1909-11)

that he completed his first orchestral rhapsody based on folk songs, the English Idyll Number 1.

In May 1910, George passed the first of three examinations for the Oxford BMus degree (music degrees in this period were often

more akin to correspondence courses), but he pursued this no further. However, work on these and, presumably his songs, which were

already published and gaining popularity, were enough to gain him entry to the

Royal College of Music where the organist Walter Parratt was his principal tutor and Charles Wood his harmony tutor. It was during this period (1909-11)

that he completed his first orchestral rhapsody based on folk songs, the English Idyll Number 1.

His mother died in early 1911 and his father, now accepting of his son's choice, gave him an allowance to continue his musical career.

However, he left the College disatisfied after a year in November 1911 and, short of money, was forced to move back in with his father in London.

The years in London were marked by a considerable increase in his productivity, and during the period 1911-1913 he was to compose two further Idylls

based on folk songs, including The Banks of Green Willow and the darker A Shropshire Lad Rhapsody

first premiered at the Leeds Festival in 1913.

He was working on a longer Fantasia for Orchestra when the outbreak of war was declared in July 1914. His last work was to help recreate the score of Ralph Vaughan Williams' London Symphony from parts; the full score had been sent to Germany

just before war had been declared and was lost. Vaughan Williams later dedicated the work to him.

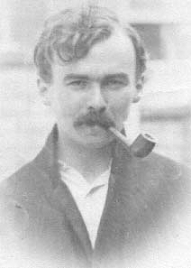

He joined up in August 1914 and was subsequently commissioned in the 13th Durham Light Infantry.

The Classical Composers Database features an image from the DLI Museum archive

of Butterworth amongst other DLI officers in May 1915, probably the last photograph of the composer.

John Rippin in his 1966 article on the composer rather pointedly notes that the war "gave him something to do",

and surviving correspondence to his father certainly suggests that George revelled in the cameraderie of his batallion.

In 1916 he took charge of his company in France after the commanding officer was wounded in battle.

That summer he was recommended for the Military Cross three times for bravery, and awarded it twice, the second time

honouring his conduct on the morning of 5th August 1916 when, during the first Battle of the Somme, he was shot through the head.

It is telling that the composer's father did not know about his decorations until he received the news of his son's death, nor did his commanding

officer know of his growing reputation as a musician.

He was buried on the front line at Pozières. As was the custom, his body would have been recovered later, but

subsequent manoevres made this impossible so no grave marking survives. His name appears on the Thiepval memorial close by, and,

in honour of his popularity with his men, a trench was named after him even before his death.

Listen to our podcast about Butterworth, including music excerpts

Back to the Butterworth navigation page

Bibliography

I recommend Peter Ward Jones' Musica Britannica (vol. 92, 2012)

edition of George Butterworth's orchestral works, which may be widely found in libraries and features some very interesting biographical and

musical details, plus a definitive transcription of Butterworth's orchestral pieces.

Autograph manuscripts of the majority of Butterworth's songs and choral arrangements can be viewed

on the British Library website at MS 54369.

Banfield, Stephen, "George Butterworth" in Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians New Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001)

Banfield, Sensibility and English Song (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985)

Barlow, Michael, Whom the Gods Love: the Life and Music of George Butterworth (London: Toccata Press, 1997)

Dawney, Michael, "George Butterworth's Folk Music Manuscripts" in Folk Music Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1976), pp. 99-113

Frogley, Alain, "George Butterworth" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Rippin, John, "George Butterworth 1885-1916" in The Musical Times, Volume 107, No. 1482 (Aug., 1966), pp. 680-682 and No. 1483 (Sep., 1966), pp. 769+771

Ward Jones, Peter, Introduction to XCII George Butterworth: Orchestral Works, Musica Britannica Trust (London: Stainer and Bell, 2012)

Wortley, Russell and Dawney, Michael, "George Butterworth's Diary of Morris Dance Hunting" in Folk Music Journal, Vol. 3, No. 3 (1977), pp. 193-207